Hi everybody!

For this week’s newsletter, the internet wasn’t much help. Or perhaps, my sleuthing skills weren’t as good. Still, there’s never a dearth of rabbit holes to disappear into. So, this time, I’ll tell you about my paternal grandfather. Dadu.

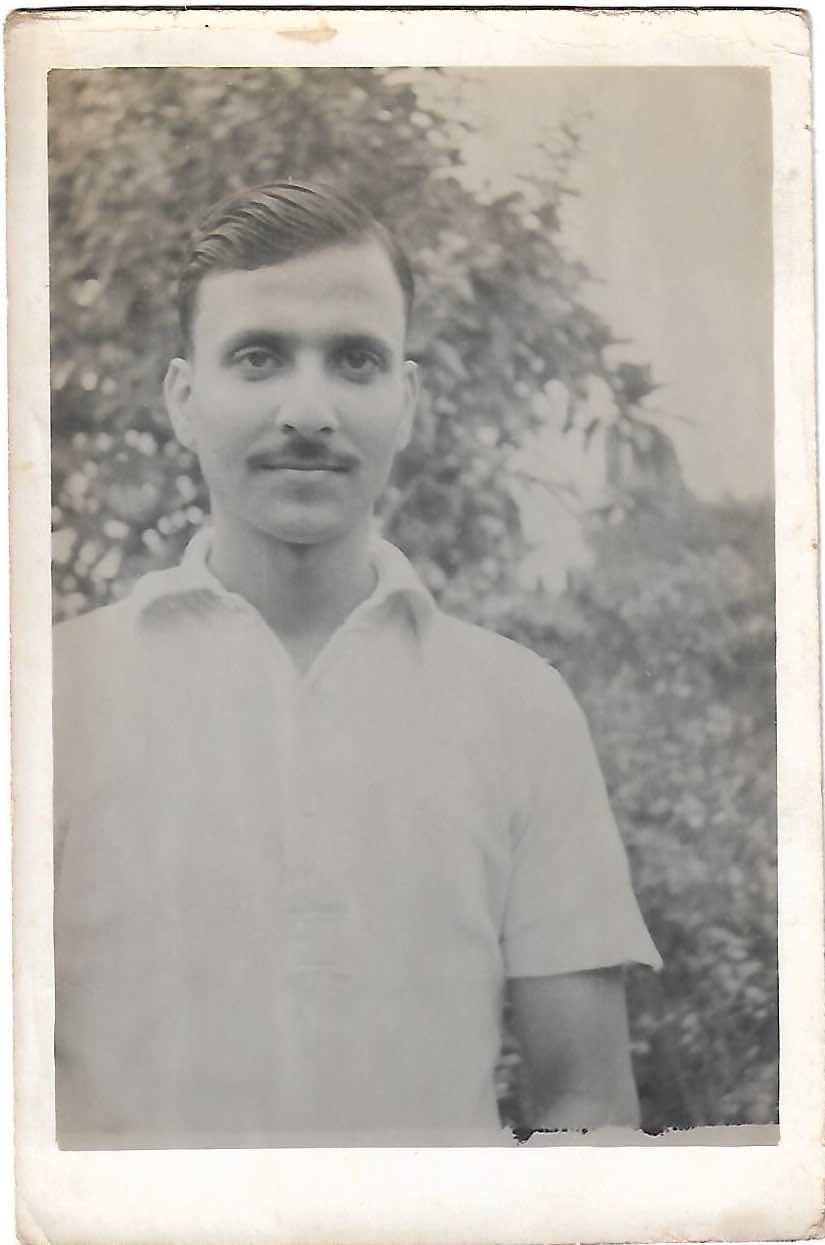

Growing up, I came to know Dadu, one summer vacation at a time. In my eyes, he was this tall, incredibly fit, striding man who went on brisk walks with a lathi in his hand — not to support himself, but just to rhythmically swing it around between his fingers. After his walk every evening, he would come back with aloo chop and egg roll from the market. Then, my brother and I would sit by his side, while he narrated endless stories about mythology. He was a brilliant storyteller. But what else was he?

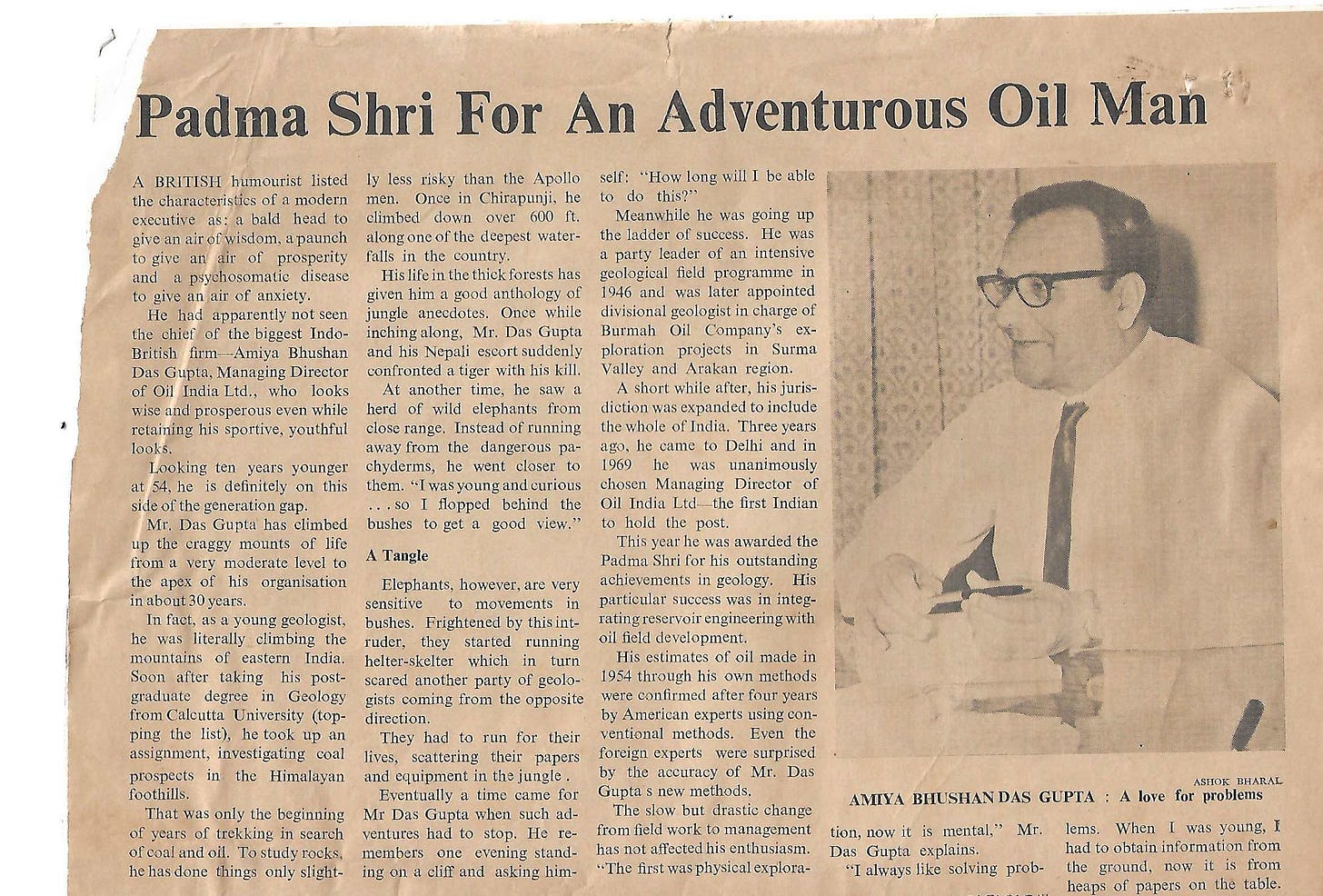

Professionally, he had been in the oil industry – I knew that. It was a world I was both curious and conflicted about. As I entered my 20s, angry about all the problems previous generations had dumped upon us, the conflicted part won over, and I tried to run away from the big bad world of oil. I became a wildlife researcher, then an environment and science writer. But now, in my 30s, I no longer see the world in clear boxes of black and white. And I feel like I’ve missed out on talking to Dadu about the geologist he was; about the life that led him to become one of the early pioneers of India’s oil exploration industry; about the work that led to a Padmashri Award in 1971.

So, I finally sat down with my dad (over the phone) and asked him – what did Dadu actually do? Turns out, there’s a lot he did. But in this newsletter, I’ll focus on his early days, where he played a key role in independent India’s first oil field.

First, some abridged history. [As told from the perspective of a geologist in the book ‘A hundred years of oil’ by Dr. SN Viswanath]

***

From the early 19th century, British military folks, who were trudging through various hilly parts of Assam, began to report that they could literally see oil ooze or bubble out of the ground as they walked through forests and villages. The local people had known of this oil—it wasn’t new to them in any way. Dadu and some his friends, for instance, had stories about the local hill tribes shoving hollow bamboo poles into hill sides and collecting oil in vessels, to be used later for cooking. There are also stories suggesting that some people were extracting kerosene from that oil.

For many British people, though, these bubbling, dark seepages were novel. And as more military reports of "oil seepages” started rolling in, there were Austrian and British businessmen who thought, well, there was money to be made here. So, they got the then British government to give them rights over some of these lands to drill wells. A lot of these wells didn’t ultimately yield much oil. That’s because seeing oil on the surface, and actually getting a good supply of this oil when you drill, are two very different beasts.

The first oil seepage that did yield some decent amount of oil was at a place called Makum in Assam. One Mr. Goodenough of a Calcutta firm led the drilling of wells there in the 1860s. Some of those wells did yield oil sporadically, but they weren’t Goodenough.

Then, came Digboi.

There are quite a few legends around the “discovery” and naming of Digboi. And it all has to do with the Assam Railways and Trading Company Limited (AR & T Co.), which, apart from constructing railway tracks and stations, was quite interested in oil.

Apparently, at one of their camps, their employees constantly smelled oil in the air. There’s also a story about how an elephant with oil-soaked legs led the railway’s men to a spot in the forest where there was oil seepage all around. In another story, the railway engineers were cooking a meal, when the ground near the camp-fire suddenly burst into flames because there was oil seeping out. Whatever the reason, the railway company applied for a license to extract oil there. To my surprise, their first application was rejected on the note that “a proposal that involves the destruction of so much timber of a reserve forest area cannot be lightly entertained”.

Of course, this sentiment to preserve the forest didn’t last. The company managed to get a go-ahead from the British government. Then they hacked their way through the forest to reach an area where a lot of oil had accumulated and solidified on the surface. That is where they drilled the first well in 1889. Legend goes that WL Lake of AR & T Co., who was heading the drilling, would ask the hired men (mostly local Assamese and Bengalis and some Punjabis) to “Dig, boy, dig” – hence, the name, Digboi. [Trust the British to come up with inane names]. Anyway, these first wells in Digboi kickstarted India’s oil industry.

In some Digboi wells, the company struck gold. But often they found dry ones that didn’t give them the oil they’d anticipated. Yet, they kept drilling. As Dr. Viswanath writes in the book, the company’s drilling frenzy was not really based on science and geology. Rather, their philosophy was that it didn’t matter where you drilled, as long as you drilled and drilled and got oil. By 1920, they had drilled 80 wells in the Digboi region that weren’t producing much oil. So another British firm, the Burmah Oil Company (BOC), decided to move in.

Let me now skip to Dadu’s role.

Dadu, formally AB Dasgupta, joined BOC in 1940 after finishing a master’s in geology from Presidency College in Kolkata. As part of BOC, he trained in Digboi, then moved around a fair bit, between Burma, Bangladesh, and northeastern India. In 1951, he returned to Digboi.

If you’ve noticed, the earlier modern oil extractions were based on what people could see on the surface. Someone would spot an oil seepage serendipitously, and if they or someone else had the money and the clout, they would convince the government to grant them the right to drill wells there.

In fact, people have used these surface oil seepages since prehistoric times. Once on the surface, lighter oils evaporate leaving behind heavier “tar”. This tar has been found on tools of Neanderthals. Earlier Homo sapiens also used tar to construct buildings and waterproof boats. Ancient Greeks would apparently set their enemies’ fleets on fire by using crude oil they got from naturally occurring oil wells around the Black sea. And the Chinese were digging for oil some 2500 years ago. There are many, many more stories like these.

As I learned, these oil seepages are mostly visible in hilly regions. This, my dad explained, is because mountains have faults/cracks/fractures/joints through which oil can very, very slowly, over millions of years, move to the surface and spill out [Digboi is in a hilly terrain]. But as we moved into the 20th century, there was greater interest in finding out more hidden reserves of oil. That was the journey Dadu embarked upon next, along with his colleagues.

Remember, this was early 1950s, just after the WWII. So, all the tools and technologies that help today’s petroleum experts estimate where oil might be and how much oil there might be, were either absent or very crude at best. There wasn’t any oil on the surface to give them clues either. But there were rocks.

Rocks are basically time machines. If you can read them, you can peep into the past, and predict a fair bit about the future. Fortunately, Dadu and his colleagues were passionate rock lovers.

They had made very precise maps of Assam’s landscape, meticulously noting down everything they observed, from the different kinds of rocks that were there on the surface to how old those rocks were, and how they were oriented and inclined. And they had done some very crude seismic surveys that gave them clues about the rocks they could expect underground, and how those rocks might be aligned.

If you’re looking for an oil field, understanding geology can tell you:

1) if there are “source rocks” below the surface — rock types that are known to have high organic matter like algae/phytoplankton, which could then be source for oil [most oil formed from phytoplankton that got buried under high temperatures and pressure, several millions of years ago];

2) if there are “reservoir rocks” that can hold onto that oil — as sediments compact, oil gets squeezed out of the source rocks, and slowly starts moving up. Reservoir rocks are the ones that then hold onto this oil because they have the pore space for storage.

3) if there’s something that restricts the oil flow. This is because oil, being lighter than water keeps moving, very, very slowly, in an upward direction. If oil keeps flowing, extracting a lot of it can be a challenge. If there’s a barrier, it helps concentrate the oil, creating a “field” of oil.

Even with all this information, predicting where an oil field might be — a place that has a large concentration of oil in one location — isn’t easy. “Imagine you’ve got a 10,000 sq. km. area,” my dad says. “Where are you going to drill there? You’re drilling a hole that’s about 20 cm in diameter. How do you decide where to drill? This was what Dadu worked out, using meagre data.”

By 1953, Dadu and his colleagues managed to predict where the next big oil field could be lying in Assam. Their focus was now on an area called Naharkatiya (translating to a place created by the cutting of Nahor trees). Naharkatiya was mostly agricultural fields, tea gardens and swamps at the time, and the geologists shortlisted two potential sites there.

“First they picked site A, then Dadu decided no, let’s first check out site B.” my dad tells me. “In those days, wells would be drilled for up to 2000 meters, but they had already gone down to 3000 meters and they hadn’t found anything. They wanted to give up and move to A, but Dadu decided that no, let’s go down a little more. And in another 200 meters, they struck oil.”

However, it wasn’t enough that they struck oil. They needed to know how much oil Naharkatiya held. The Digboi refinery was too small and new refineries were needed. But the government needed assurance of oil supply for at least 15 years to make the construction of the refineries worthwhile. Dadu, using the limited data he had, pioneered studies that showed that Naharkatiya could yield 3 million tonnes per annum (mtpa), enough to supply the refineries for 15 years at least. With the calculations done, he told the government to go ahead with the planned refineries in Guwahati and Barauni. This way, Naharkatiya became independent India’s first oil field. And it supplied oil to the refineries not for 15 years, but continues to produce oil even today. Since then, many other big and small oil fields have been discovered in Assam, some by Oil India Limited, that Dadu eventually became the first Indian managing director of, and some by ONGC — all of them keeping the previous generations’ oil dream alive.

***

PS: This story about the beginning of my grandfather’s journey was based on my dad and Dadu’s colleagues’ perspectives. Geologists’ perspectives. And I wanted to understand what it took for geologists at that time to actually find places where you could drill for oil.

Of course, you can’t disassociate science from politics and people. Extraction of oil undeniably changed our country and each of our lives. Some good came from it, but it also brought in the bad. I’m not getting into these in this newsletter—maybe I will some day. Meanwhile, here’s a book I started reading recently about how oil exploration and extraction has shaped lives in Northeast India: Living with Oil and Coal: Resource Politics and Militarization in Northeast India

PPS: If you like geology, may I recommend the following two newsletters/blogs:

The Geosophy Newsletter by Devayani Khare.

Rapid Uplift by Suvrat Kher.

***

That’s it. This week, I shared a bit of my past with you [birthdays have a way of making you think about the past]. Next week, I’ll have some internet fun coming your way. Subscribe if you want the newsletters delivered to your inbox. If you want to talk about oil, or weird things you learned while you were procrastinating, follow me on Twitter @ShreyaDasgupta. Or send me an email: shreya.dg [at] gmail.com